ADMIN NOTE: I apologize for the lengthy absence. I was out last week with a bout of strep. I have recovered and am back to the publishing schedule. - M.S.

During my downtime last week, I read Theda Skocpol’s States and Social Revolutions (1979), a comparison of the revolutions in France, Russia, and China.

In this post, I’ll compare some of the book’s points to the “revolutionary environment” of today.

Concept: One of her main points in the Introduction is that revolutionaries don’t cause their own revolutions.

Explanation: Revolutions only occur when citizens or subjects are open to alternatives to the existing government.

Alternatives like a revolutionary ‘government in waiting’ or an insurgent shadow government can exist, but their existence alone doesn’t win them the support required to become the next legitmate government.

Support for an alternative only comes through significant and usually prolonged government failure to solve real problems.

History shows more often than not that citizens/subjects are willing to endure protracted grievances, oppression, and great moral injury without supporting revolution. Revolution would be far more prevalent if that weren’t true.

Citizens or subjects must believe that these government failures will not be solved through reform (e.g., can’t or won’t be solved through a future election or new leader), and that the pain induced by government failures must be greater than the risk incurred by supporting a revolutionary alternative. (One thing that’s kept the U.S. relatively stable is two-, four-, and six-year terms, which ostensibly provide a routine opportunity for reform and greatly diminish demand for violent revolution. Change™ is always less than four years away!)

Revolutionaries can foment anger and resentment among the people but they can’t cause the government to ignore or exacerbate the people’s real problems.

Skocpol doesn’t use this analogy, but we can think of revolution like a single action pistol.

A revolutionary leader or vanguard cocks the hammer, but a crisis pulls the trigger.

That crisis represents a “revolutionary rupture” where mass mobilization and organized political violence can begin. (There are estimates that support from just 15-25% of the population is enough to sustain an insurgency, for instance.)

And I think this is what Skocpol means by saying that revolutionaries don’t actually cause revolution, which is a basic but necessary point to make.

I bring this up for a couple reasons.

First, there were predictions of widespread chaos this summer, on the order of 2020.

I’ve been doubtful about that scenario. Last November, my baseline scenario was a repeat of the low level unrest of 2016. At the time, I didn’t foresee enough accelerators of conflict for a revolutionary rupture like we saw in 2020.

And repeated attempts to foment a trigger event this year have failed because of the relatively low starting social temperature. A pot doesn’t start boiling at 95°F, which is about where we are.

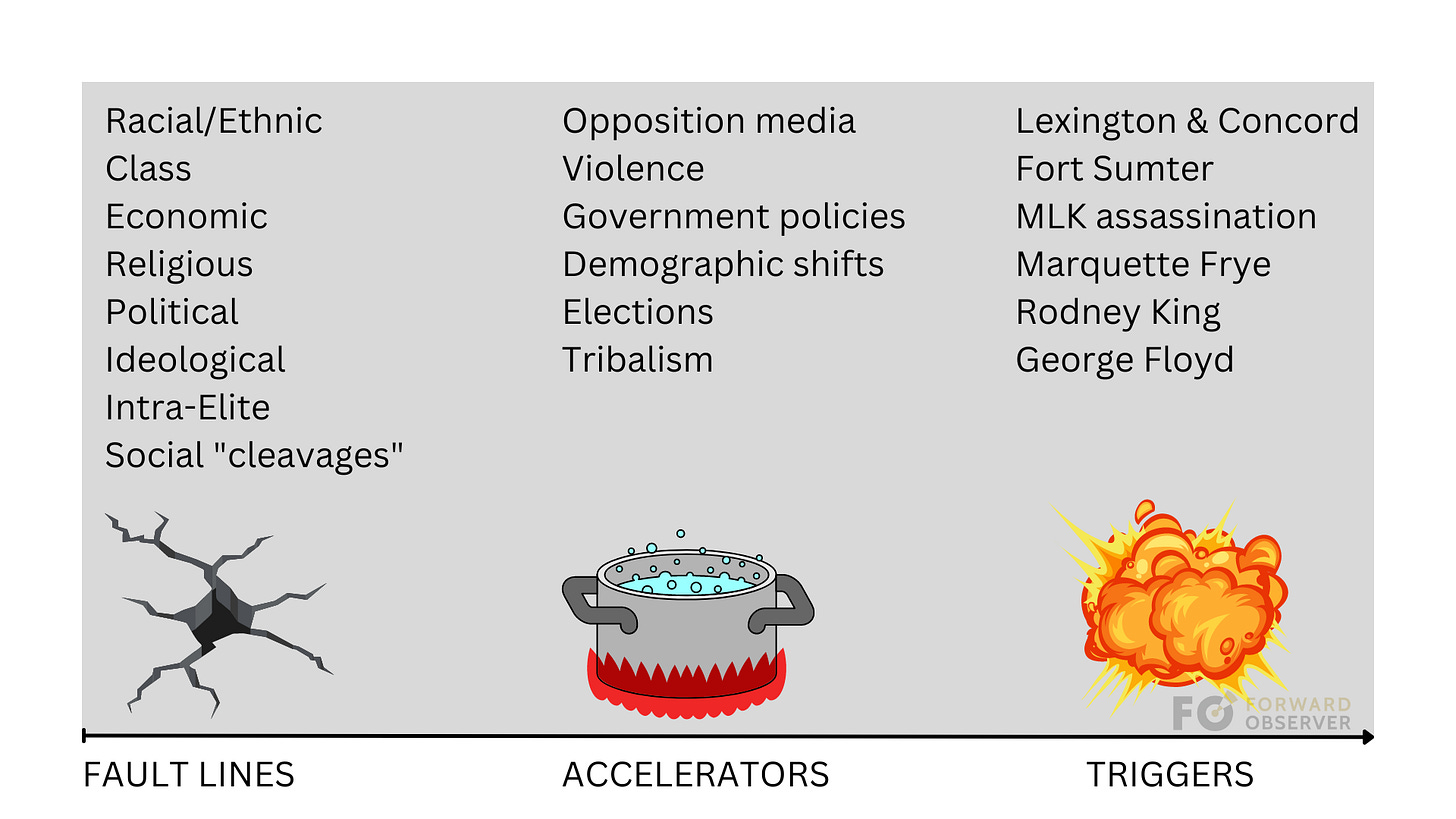

Any time we talk about low intensity conflict, we’re dealing with three factors: faultlines, accelerators, and triggers.

Faultlines are structural divisions within a society. They could be racial/ethnic, class-based, ideological, etc. (There could even be local faultlines, such as zoning plans, law enforcement activities, etc., which pit one part of a community against another.)

Accelerators are events or conditions that turn the temperature up or get the tectonic plates of society moving ahead of an earthquake. The 2020 pandemic and election season were accelerators, as was the general unrest during the Trump administration.

Finally there are triggers — those “revolutionary ruptures” that cause mass mobilization and organized political violence.

Heading into the 2024 election season, inflation, the border invasion, Trump legal troubles, and Gaza are the primary accelerators, but they don’t have the same direct impact on society as the pandemic, the lockdowns, and recession. We are not boiling yet.

For a revolutionary rupture to occur, there must be some national crisis that’s more painful than the risk undertaken to actively oppose a government or social system, which was the goal of the revolutionary class in 2020.

The second reason I bring up this portion of the book is because there’s a misunderstanding of where we are in this revolutionary cycle.

There are unfortunately attempts to characterize today’s relatively low level protests and campus occupations as “overt paramilitary action,” which is absurd. I’ll explain why.

The concept of People’s Revolution, the most common form of communist revolution, has three distinct phases. Other communist revolutionaries have described four and five phases, which I’ll also outline below*.